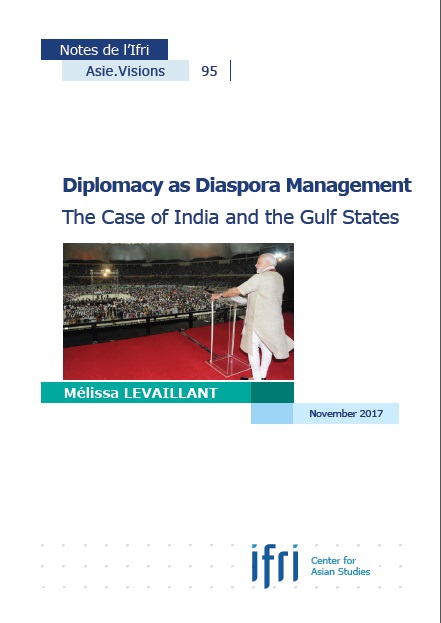

Diplomacy as Diaspora Management: The Case of India and the Gulf States

In today’s world, diaspora management and diplomacy have become increasingly enmeshed, reflecting the growing interconnections between domestic and international issues.

About eight million Indian workers are present in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, and send about $35 million worth of remittances per year to India. 80% of these Indian workers in the Gulf are low-skilled and semi-skilled temporary workers, and many suffer from exploitation and abuse that derive from the Gulf kafala or sponsorship system. Because of their size and complexity, these migration flows of Indian citizens to the Gulf countries have an impact on the diplomacy New Delhi conducts in the region.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the issue of the Indian diaspora has been raised on India’s diplomatic agenda. A Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs (MOIA) was created in 2004 and then merged with the Ministry of External Affairs in 2015, with the aim of engaging and connecting with the Indian diaspora abroad. Elected in 2014, Narendra Modi has put even more emphasis on the need to tap into the migrants’ potential role in promoting India’s interests abroad, and to encourage inward investments from wealthy Non-Resident Indians living in the West.

Nevertheless, the government has largely failed to ensure the protection of the most vulnerable migrants, many of whom are located in the Gulf. This can be explained to a large extent by the deficiencies of India’s legal protection system that dates back to the 1983 Emigration Act. The initial objective of this Act was to systematize and regulate emigration of unskilled and low-skilled Indian workers for contractual overseas employment, and to avoid their exploitation. However, the Indian government has failed to regulate and monitor the practices of private recruiting agencies, and this institutional framework has been inadequate to fight against corruption and exploitation of labor.

Yet, because of regional instability in the Middle East and heightened domestic pressures, Indian diplomats are increasingly considered as responsible for the security and safety of their citizens abroad, and their capacity to develop appropriate responses has become a legitimacy test for the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA). In this context, the Indian government has recently developed ad hoc policies that put the emphasis on protecting workers and implementing welfare initiatives abroad. In the Gulf region, new mechanisms aimed at improving the protection of migrants were put in place by the MOIA, in coordination with the MEA and Indian missions abroad. Indian embassies and consulates in the Gulf region have recently been modernized, with the creation of new consular and social services delivered to the Indian diaspora.

But the limited budget and human resources of the MEA have strongly constrained India’s ability to adapt to the new requirements of migration management, and the Indian diplomatic and consular missions in the Gulf are not able to provide adequate services to their nationals. Added to this resource issue is the important fact that India’s diplomacy in the Gulf rests on a paradox: although diplomats have made increasing efforts to promote Indian migrants’ rights, their political priority is directed towards maintaining emigration flows. Indeed, remittances sent by the Indian workers in the Gulf play a vital role in the economic development of several Indian states. This strongly impedes diplomatic risk-taking during negotiations with the Gulf States on labor rights, as Indian diplomats are afraid that too much activism could lead to a temporary ban on Indian workers. Today, there is no concrete evidence to show that bilateral agreements signed between India and Gulf countries have improved the protection of low-skilled Indian workers, and India’s diplomacy has also been very limited at the multilateral level.

Finally, the rise of diaspora management on India’s diplomatic agenda has forced the MEA to strengthen its performance by enlisting the help of non-state actors. In the Gulf, Indian diplomats rely heavily on the financial and material support provided by local Indian associations, which gather highly skilled workers and businessmen who are involved in charity works. This creates a favorable context for the politicization of a few Indian diplomats and the development of collusive transactions in the region, while constraining the conduct of other diplomatic activities.

Download the full analysis

This page contains only a summary of our work. If you would like to have access to all the information from our research on the subject, you can download the full version in PDF format.

Diplomacy as Diaspora Management: The Case of India and the Gulf States

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analyses

RAMSES 2024. A World to Be Remade

For its 42nd edition, RAMSES 2024 identifies three major challenges for 2024.

France and the Philippines should anchor their maritime partnership

With shared interests in promoting international law and sustainable development, France and the Philippines should strengthen their maritime cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. Through bilateral agreements, expanded joint exercises and the exchange of best practices, both nations can enhance maritime domain awareness, counter security threats and develop blue economy initiatives. This deeper collaboration would reinforce stability and environmental stewardship across the region.

The China-led AIIB, a geopolitical tool?

The establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016, on a Chinese initiative, constituted an attempt to bridge the gap in infrastructure financing in Asia. However, it was also perceived in the West as a potential vehicle for China’s geostrategic agendas, fueling the suspicion that the institution might compete rather than align with existing multilateral development banks (MDBs) and impose its own standards.

Jammu and Kashmir in the Aftermath of August 2019

The abrogation of Article 370, which granted special status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), has been on the agenda of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for many decades.