Rethinking the Confederate Legacy

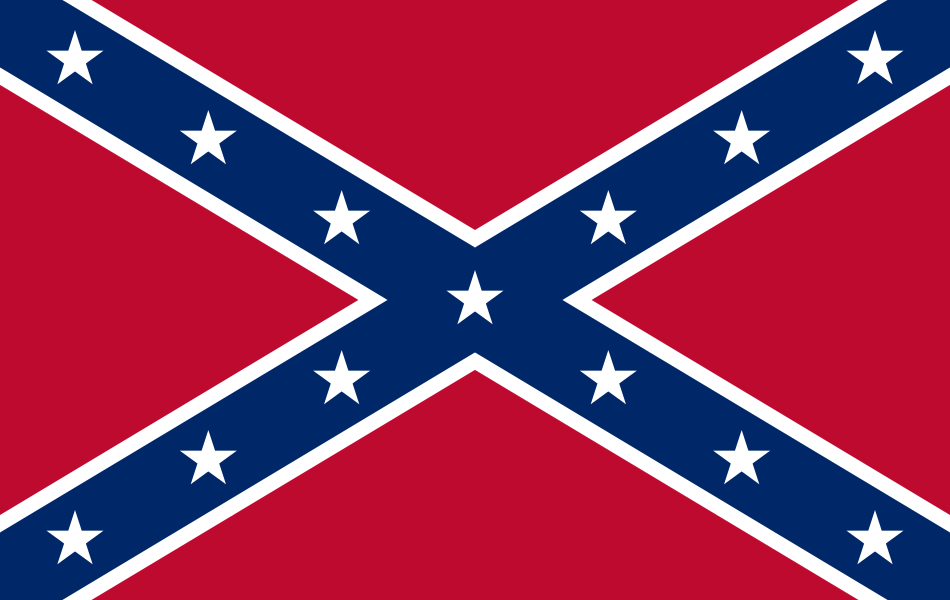

The battle flag of General Robert E. Lee’s famed Army of Northern Virginia, commonly known as the Confederate Flag or the Southern Cross, has become the symbol of the 1861-1865 Southern secession and the most widespread sign of Southern regional identity. Today it can be found flying across the South and on everything from clothing to bumper stickers.

Many other reminders of the Confederacy still dot the region. Groups dedicated to preserving the Confederacy’s legacy wove memorials, streets, schools and flags honoring Southern defiance into the landscapes of many Southern towns and cities. As a result, the Deep South is scattered with schools named after General Robert E. Lee, parks named for Confederate President Jefferson Davis and roads named after other Confederate heroes like General Stonewall Jackson. North Carolina has more than 50 Confederate memorials in front of its county courthouses alone and seven Southern states have flags that reference the Confederacy. [1]

The shooting of nine African-Americans in a Charleston church on June 17 sparked a reevaluation of these symbols’ meanings in American society, however. In response to the attack, a number of major retailers including Amazon, EBay and Wal-Mart pulled products featuring the Confederate Flag from their shelves. South Carolina voted to remove the banner from a monument on the statehouse grounds, and a number of Mississippi legislators have called for a new state flag that excludes the Southern Cross.

In other words, 150 years after the Confederacy’s dissolution at Appomattox in 1865, the memory of the American Civil War, largely divided along regional and ideological lines, remains an issue.

Diverging Narratives

The Civil War, or the War of Northern Aggression as some Southerners call it, is still fought every day in schools and towns across America. Textbooks in Southern schools, generally written to accommodate Texas’ curriculum guidelines, often underemphasize slavery as one of the war’s causes, instead opting for a narrative centered on federal overreach and states’ rights while promoting Southern exceptionalism. In contrast, children in many other states use books that conform to Californian standards and learn that slavery tore the country apart, eventually leading the Southern states to secede and pitting the two regions against one another.

The traditional Southern interpretation of the Civil War does not stem from a modern conspiracy to promote an antiquated racial order but rather a narrative established just after the war that has become known as the “Lost Cause”. This myth re-imagines a Confederacy that fought nobly to protect its blissfully simple and chivalrous way of life in the face of federal tyranny. The South could not defeat the Yankees but it fought bravely and admirably for a just cause. Slavery is often either downplayed as a minor element or even glorified as a fair practice. Think Gone with the Wind. For generations, many Southerners have been indoctrinated with this mentality. It colored Southern reactions to events from the Reconstruction Period to the Jim Crow Era through the Civil Rights Movement to today.

In light of these diverging narratives, it is no wonder that Northerners and Southerners do not see eye-to-eye on the Confederate flag issue. Whereas in the North the flag has a shock value and is looked down upon as a symbol of racism and rebellion, the excess of Confederate memorialization across the South desensitizes many to the antebellum South’s cruel reality. Additionally, as the South repeatedly comes in last in wellbeing and economic indicators, a strong sense of cultural pride and exceptionalism maintains morale.

A Gallup Poll taken this month shows how differences of opinion match partisan, racial and educational divides - beyond geography. When asked if Southern governments should stop the practice of displaying the Confederate Flag, 73% of African-Americans said yes versus 41% of Whites. The difference is just as stark when the poll takes political affiliation into account, with 69% of Democrats but only 27% of Republicans agreeing that states should remove their flags. Lastly, preference for removing Confederate displays increases with educational attainment as only 37% of respondents with a high school degree or less promote removing the flag, in contrast to 54% of college graduates and 67% of those with a postgraduate education.

The Flag Comes and Goes

Following the Civil War, the flag fell from the public sphere as the Northerners overseeing the reconstruction process viewed it as a sign of treason. However, the collapse of Reconstruction in the 1890’s led to the Southern Cross’s reemergence and solidification as the Confederacy’s preeminent symbol. This transition coincided with the beginning of the Jim Crow era and the resurgence of White political power in the South. Given that historians often regard this period as the height of post-slavery racial violence, one would be hard-pressed to argue that the period’s resurgence in Confederate pride was void of White supremacist undertones.

As Confederate veterans began to die, the flag’s significance once again began to wane, only to return again in 1948 as the official symbol of the Dixiecrats, a political party led by South Carolina Senator Strom Thurman that split from the Democratic Party in opposition to its increasingly progressive stance on civil rights issues. In light of the Dixiecrats’ racist policies, the flag was once again soiled by racism. It remained a segregationist symbol throughout Southern integration. In fact, the flag only appeared above the South Carolina statehouse beginning in 1962 in reaction to the Civil Rights Movement.[2]

Today, the majority of those Americans who display the Confederate flag do so not out of hatred but out of a genuine desire to express regional pride and identity. Nonetheless, Americans cannot responsibly continue to ignore the fact that the flag has resurfaced repeatedly as a symbol of racial intolerance and White supremacy. When incorporating the pattern into a new national flag for the Confederacy in 1863, William Thompson commented that the design “is significant of our higher cause, the cause of a superior race” and in doing so tied the symbol to White supremacy from the start.

Hateful extremists continue to champion the Southern Cross as a celebration of the despicable values for which they stand. In fact, the debate over the appropriate use of the flag only reignited in response to the terrorist attack in Charleston after pictures emerged of the shooter celebrating the banner as a symbol of White supremacy. Those images convinced Southern leaders that although some wield the Southern Cross without hateful intent, the flag’s distasteful duality makes it inappropriate for the local or state governments to endorse through public display.

A New Southern Collective Memory

Critics of South Carolina’s decision to remove the Confederate flag from a memorial on the statehouse grounds worry that it is the first step toward cleansing Southern history while losing regional identity in the process. In contrast, proponents view it as an important stride toward racial reconciliation. The flag lies somewhere between those two views and therefore raises the important question of how to preserve regional identity while promoting a unified and historically accurate narrative. Two steps could yield this result: re-contextualizing Confederate memorialization and promoting a historical narrative that includes a more diverse range of experiences.

First, states can begin re-appropriating Confederate symbols and memorials by reconsidering the contexts in which they are constructive. For example, elementary schools named for Confederate generals may lead children to internalize such figures as heroes and should therefore be renamed, whereas, a monument, if properly explained with historical markers, can serve as a useful educational tool. Leaving memorials and symbols without explanation facilitates the Lost Cause narrative whereas re-contextualizing them from celebratory to historical reminders would preserve the past and regional identity both tactfully and constructively.

Secondly, the United States fails to properly recognize and commemorate the achievements of minorities. Cities too often relegate streets commemorating famous African-Americans to poor neighborhoods dominated by minorities. Holidays such as Juneteenth, a day commemorating the end of slavery in the United States in 1865, remain virtually unknown. Meanwhile, the narratives taught in schools are dominated by White men and underemphasize minority experiences. Promoting African-Americans to their rightful place in history and presenting alternative narratives can ensure that collective memory reflects a common history rather than simply that of the White majority. Such a shift would help unite the country around a common collective memory by giving African-American history proper attention and in doing so completely discrediting Lost Cause ideology.

Looking Ahead

The country is starting to realize that the carefully constructed Southern culture and identity does not reflect the region’s increasing inclusivity. It harkens back to the same history of intolerance and racism that most want to escape. But unlike too many times before, the African-American community is speaking and the South is listening. The outcry against the Confederate Flag in the wake of the Charleston attack represents a step toward unifying the country around a common narrative by recognizing that the flag offends many and as such should be used sparingly. Despite this progress the discussion will continue as nation-wide support for the Confederate Flag as a symbol of Southern pride is in decline but remains above 50%.[3]

The debate doesn't end at the flag but rather starts now with an honest conversation about collective memory and the creation of a Southern identity that all Southerners, regardless of race, can come to terms with and be proud of.

[1] http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2015/06/21/how-the-confederacy-lives-on-in-the-flags-of-seven-southern-states/

[2] http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/06/confederate-flag-south-carolina-history/396695/

[3] http://www.gallup.com/poll/184040/democrats-views-confederate-flag-increasingly-negative.aspx?version=print

Also available in:

Regions and themes

ISBN / ISSN

Share

Download the full analysis

This page contains only a summary of our work. If you would like to have access to all the information from our research on the subject, you can download the full version in PDF format.

Rethinking the Confederate Legacy

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analysesAUKUS Rocks the Boat in the Indo-Pacific, And It’s Not Good News

For anyone who still harbored doubts, Washington made crystal clear from the announcement of the new trilateral alliance with Australia and the UK (AUKUS) that countering China is its number one priority, and that it will do whatever it takes to succeed. Much has been said about the consequences of AUKUS on the French-US relations, but the strategic implications for the Indo-Pacific nations (including France), and for China especially, are also critical to consider.

Washington-Téhéran : l'élection de Joe Biden change-t-elle la donne ?

The recent assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the father of Iran's nuclear program, echoes that of Qassem Soleimani in January 2020 and illustrates the policy of "maximum pressure" which has prevailed these past four years. In this context, Joe Biden's election gives rise to high expectations for the appeasement of U.S.-Iran relations.

L’inégalité du Collège électoral aux États-Unis : comment réparer la démocratie américaine ?

Since the start of the 21st century, the flaws of the Electoral College, which completes the election process of the president of the United States by indirect universal suffrage, are the target of stronger than ever criticism.

Trade Wars: A French Perspective

The Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum announced by the United States in March would, if applied, have little direct impact on the French economy, but rather point toward a broader trend of protectionism and economic nationalism and a widening gap in transatlantic relations that is likely to have far-reaching implications for France.